Mahatma Gandhi: Apostle of peace and his messages in ink

“My life is my message,” once said Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi – Mahatma Gandhi as he is known the world over. India's national leader, reformer was a great communicator. He connected with the masses, mobilised a whole country against the mighty British Empire and spearheaded India's quest for freedom.

He recognised the power of effective communication to garner popular support.

“Gandhi was successful because he had a latent skill in communication that surfaced in South Africa, where he had gone initially to set up practice as a lawyer,” said Prathit Misra, second secretary, High Commission of India in Jamaica. “What began in South Africa gave him the impetus to spread his message to the masses and rally millions of Indians.”

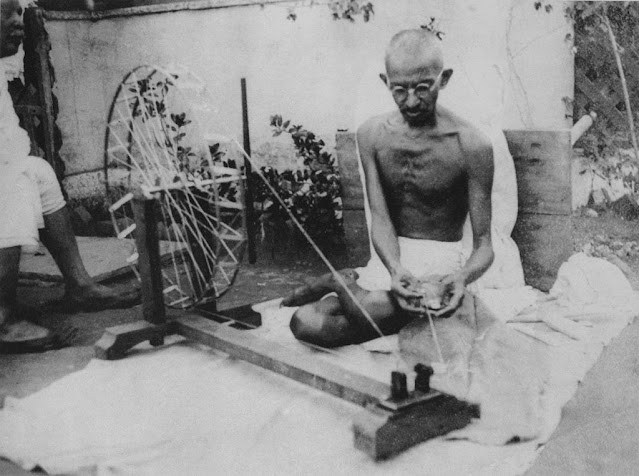

Gandhi was a prolific writer and believed in the power of pen over the sword – promoting the principles of non-violence. To the world, the images of Gandhi – a frail-framed, modestly clad gentleman, walking with a stick – are the most visible. One may not find many of him penning a letter or editing a paper. In his serene moments, his thoughts flowed from the pen on to paper.

“Mahatma Gandhi believed that it was important to inform and educate the masses, and there was no better way than newspapers,” Misra said.

From South Africa to India, Gandhi's journalistic voyage birthed several publications. We chronicle the journalistic journey of Mahatma Gandhi in his birth month (he was born October 2, 1869).

Indian Opinion

Gandhi started Indian Opinion in South Africa, which was published between 1904 to 1915. This paper became a critical tool to fight racial discrimination and gain civil rights for the Indian community in the country.

The initial aim was the education of Europeans in South Africa about issues facing the Indian community. Published in Indian languages – Gujarati, Hindi, and Tamil – and English, Indian Opinion highlighted the poor conditions faced by indentured labourers, challenged laws of the state, and published news about Indians in the colonies before the public in India. This was to be a stepping stone for Gandhi when he returned to India and immersed himself in the country's freedom struggle. He once said: “Satyagraha (hold firmly to truth – a name that Gandhi gave to the non-violent movement) would have been impossible without Indian Opinion.”

In India, he would publish Young India, Harijan (children of God), and Navjivan (new life).

Young India was an English weekly journal published from 1919 to 1931. Through this publication, Gandhi popularised his thoughts and encouraged people to embrace non-violence in their fight against the British rule. Navjivan, which was published in his native language ,Gujarati, was established with the same guiding principles.

Harijan

In 1933, Gandhi established a weekly newspaper, Harijan, in English. Gandhi gave this name Harijan to the untouchables in India's social hierarchy. Harijan was in publication till 1948, the year Gandhi was assassinated. He published Harijan Bandu in Gujarati and Harijan Sevak in Hindi. These publications focused on social and economic issues facing the masses.

Gandhi also authored several books:

The Story of My Experiments With Truth (Autobiography)

The Story of My Experiments With Truth chronicles Gandhi's life from early childhood to 1921. From birth and parentage, Gandhi reminiscences about his childhood, child marriage, relations with his wife and parents, experiences at the school. Gandhi details his stay in London as a student, his effort to be like the English gentleman, experiments in dietetics. The story moves to South Africa, where he faced colour prejudice, his quest for dharma, social work in Africa, his return to India, his slow and steady work for political awakening and social activities.

In the preface, Mahatma Gandhi writes: “It is not my purpose to attempt a real autobiography. I simply want to tell the story of my experiments with truth, and as my life consists of nothing but experiments, it is true that the story will take the shape of an autobiography. But I shall not mind if every page of it speaks only of my experiments.”

Gandhi's experiences in South Africa had a profound and life long impact on him. He faced a sting of humiliation and the incident at Maritzburg. When Gandhi, as a matter of principle, refused to leave the first class compartment, he was thrown off the train. Gandhi also continued to seek moral guidance in the Bhagavad-Gita (a Hindu holy scripture), which inspired him to view his work not as self-denial at all, but as a higher form of self-fulfillment.

The development of the Gandhian methods of non-cooperation and civil disobedience in South Africa and their implementation during the non-cooperation movement in India are also mentioned.

Hind Swaraj

|

| Mahatma Gandhi - Wikimedia Commons |

In the book, Mahatma Gandhi outlines four themes. First, he argues that it is not enough for Indians to adopt a British-style society, but transform the society according to Indian values.

Gandhi also argues that Indian independence is only possible through passive resistance. He says, “The force of love and pity is infinitely greater than the force of arms.” Mahatma Gandhi suggests adopting Swadeshi (self-reliance) by Indians, meaning that Indians use only Indian products, thus hitting at the economic strength of the British. Gandhi presented a cogent critique of the Western civilisation.

Gandhi was a prolific writer who connected with the masses – his writing was devoid of any flamboyance – and like the man himself, his communication was simple, to the point, and relatable.

“He never aimed at a style or used flowery words merely to please the ear,” said Misra. “He had a forceful style of his own which mirrored his hopes and faith, his sorrows and disappointments.”

Gandhi's messages live on.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment